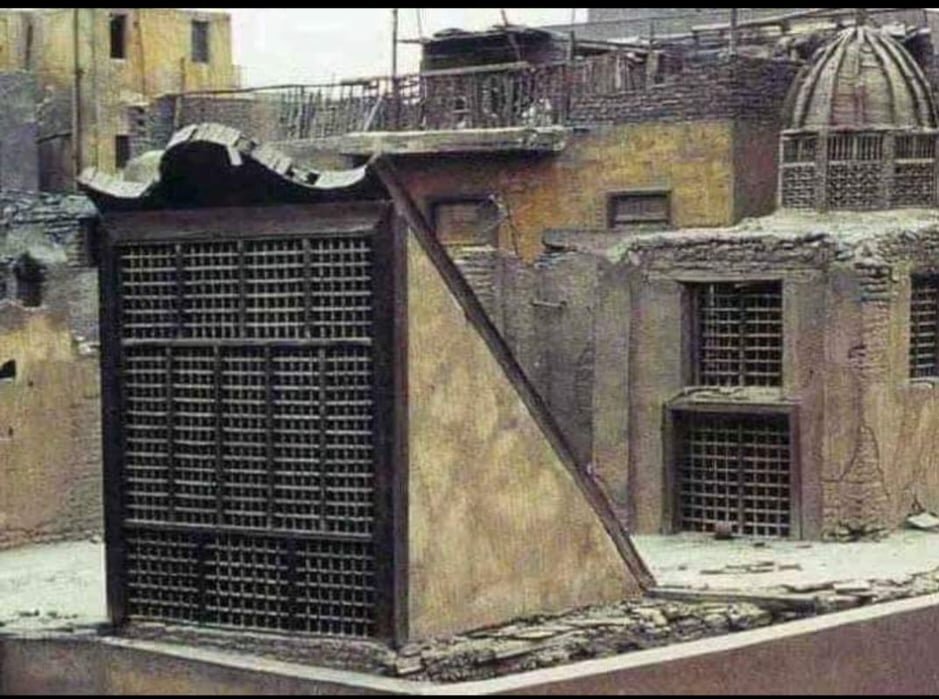

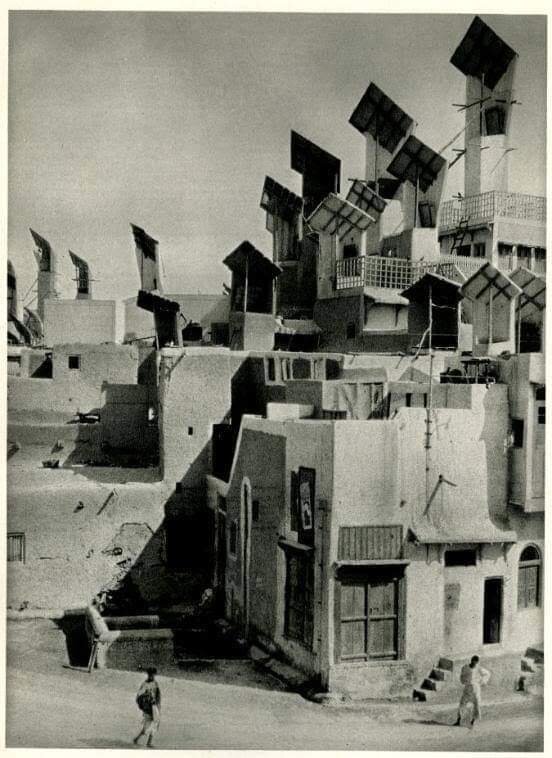

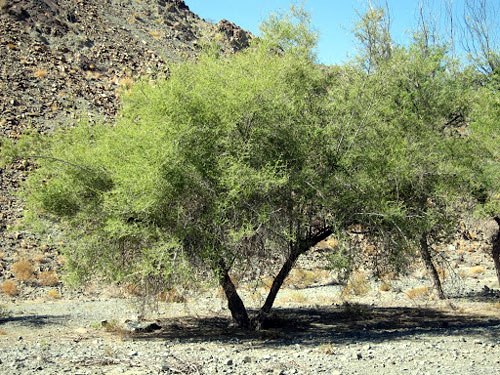

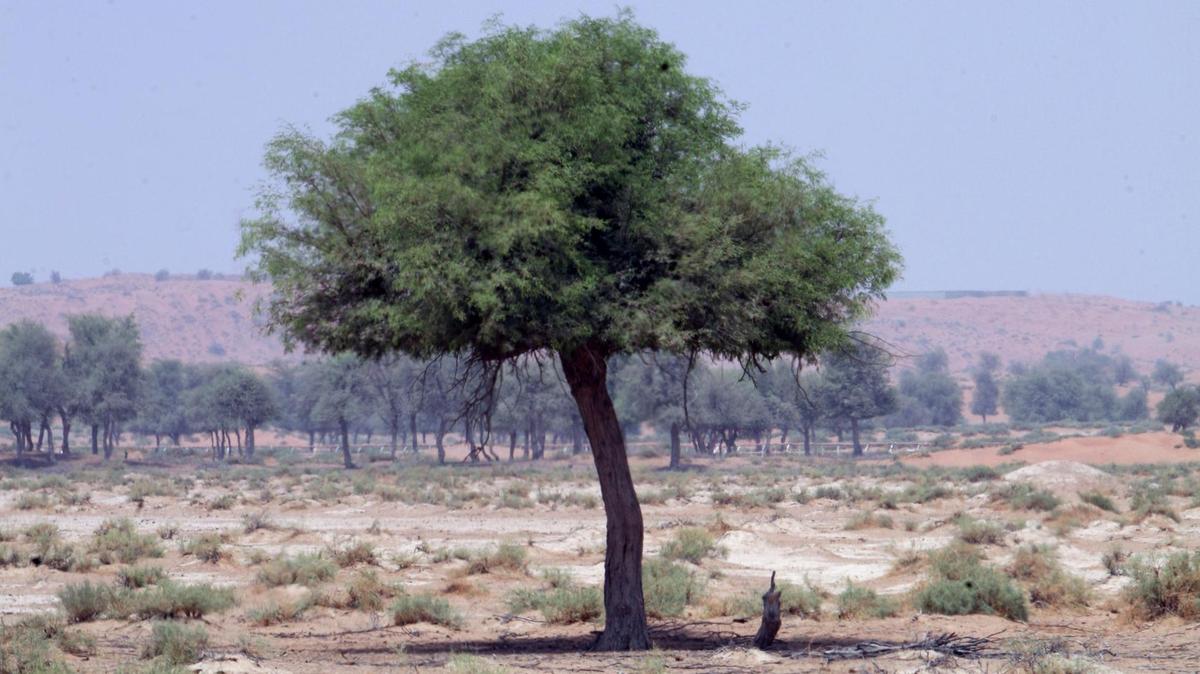

Yes, the Arabian Peninsula is hot, unbearably hot, so hot that at times I question whether or not civilization belongs in this part of the world, but the fact of the matter is: people have lived in these areas for centuries under these difficult weather conditions. People of the peninsula relied on their feet to get around their cities and townships. Cities were dense, sikkak provided shading and additional spaces for walking, marketplaces provided shade for customers and passersby. People built malaqif (sing. Milqaf, windtowers) to cool their houses and mosques. Today, with science and technological advancements, using proper street orientation, a system of sikkak, and providing shading with trees native to the region, it is possible to repopulate our cities with pedestrians despite the heat. While the heat and weather certainly make walking less comfortable and less of an appealing option to navigate the city, the lack of infrastructure and pedestrian-oriented design bars people from walking in the city. Municipalities within the region need focus on planning at a microscale, focusing on small districts and neighborhoods, ensuring the scale of planning is that of the pedestrian such that a safe and comfortable environment can be ensured. The region is suffering from a health crisis. Obesity rates are at the highest they have historically been, cardiovascular diseases are on the rise, all of which is further stimulated by the unhealthy automobile-dependent lifestyle that the Khaleeji urban form has perpetuated. The world is suffering from an environmental crisis, countries of the GCC top the world’s lists in carbon footprint per capita, of which transportation by private automobile is one of its biggest contributors. Walking, along with public transit, should be as effective, if not more effective than the automobile if we want to make it a more competitive and attractive alternative option for transportation.

On a final note, it’s really only unbearably hot between May and September, while the weather is surprisingly nice for the rest of the year.

Additional Reading:

Harb, D F. “Walk-ability Potential in The Built Environment of Doha City,” n.d., 15.

Kamel, Mohamed Atef Elhamy. “Encouraging Walkability in GCC Cities: Smart Urban Solutions.” Smart and Sustainable Built Environment; Bingley 2, no. 3 (2013): 288–310. https://doi.org/10.1108/SASBE-03-2013-0015.

Koerniawan, Mochamad Donny, and Weijun Gao. “Thermal Comfort and Walkability In Open Spaces of Mega Kuningan Superblock in Jakarta.” In ResearchGate, Vol. 3. Venice, Italy, 2014. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.4388.5766.

Rahman, Muhammad Tauhidur, and Kh Md Nahiduzzaman. “Examining the Walking Accessibility, Willingness, and Travel Conditions of Residents in Saudi Cities.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 4 (14 2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16040545.

Scoppa, Martin, Khawla Bawazir, and Khaled Alawadi. “Walking the Superblocks: Street Layout Efficiency and the Sikkak System in Abu Dhabi.” Sustainable Cities and Society 38 (April 1, 2018): 359–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.01.004.

Shaaban, Khaled, and Deepti Muley. “Investigation of Weather Impacts on Pedestrian Volumes.” Transportation Research Procedia, Transport Research Arena TRA2016, 14 (January 1, 2016): 115–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2016.05.047.

Shaaban, Khaled, Deepti Muley, and Dina Elnashar. “Evaluating the Effect of Seasonal Variations on Walking Behaviour in a Hot Weather Country Using Logistic Regression.” International Journal of Urban Sciences 22, no. 3 (July 3, 2018): 382–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2017.1403363.

Silva, Joao Pinelo, and Aamal Z. Akleh. “Investigating the Relationships between the Built Environment, the Climate, Walkability and Physical Activity in the Arabian Peninsula: The Case of Bahrain.” Edited by Silvio Caputo. Cogent Social Sciences 4, no. 1 (January 1, 2018): 1502907. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1502907.