The Villa in a Khaleeji Context: The Role of Regulations in Erasing Indigenous Building Practices

“A Qatari house in Al Dafna area” - Nayla Al-Naimi in The Morphology of Urban Qatar Homes

Megaprojects in the Khaleej, particularly in Qatar, focus on branding themselves with a ‘new architectural language’ that is uniquely Qatari, Khaleeji, Arabic, or Islamic. This is especially true with the urban revitalization project ‘Msheireb Downtown Doha’ where a new architectural language was one of its many pillars in creating a new identity for Doha based on ancient architectural practices. Other megaprojects in the city market themselves as showing a cultural flair as well, the architecture of the Al Bayt and Al Thumama Stadium, which are set to host the World Cup in 2022, were directly influenced by Qatari culture. Architects, designers, and government officials are keen on injecting cultural influences within the Qatari urban space whenever it is possible. However, the architecture of government-sponsored megaprojects only plays a small piece of the puzzle in the way architecture is experienced in the Qatari urban form. A quick look at a land-use map of Doha and its surrounding municipalities (or a satellite image for that matter) shows that the bulk majority of land use is predominantly low to low-medium density residential housing. This problem is not unique to Doha, the bulk majority of cities in the Khaleej are dominated by single-family houses and villas. The ‘villa’ is not native to the region, yet it dominates our cities. The word typically describes a large and luxurious country house, particularly in Continental Europe. Yet the villa has forced its way into our vernacular speech, as well as our cities. The injection of an architecturally foreign mode of living directly clashes with the direction that the government is steering towards. This begs a multitude of questions to be asked: How did we get here? What are the socio-cultural and environmental consequences of the villa in this context? Is there room to reappropriate the villa? And do zoning code and building regulations play a role in the way tastes are being shifted towards the villa?

Msheireb Downtown Doha

The Msheireb Downtown Doha project prides itself on merging modern and traditional architectural styles in its neighborhoods, and set out to create a modern architectural style that is uniquely Qatari

Like most things in the Khaleeji urban landscape, much of the shift in our housing patterns owes itself to modernization policies set forth by the British protectorate, as well as newfound wealth from oil. Prior to the mid-20th century, courtyard houses were the preferred mode of living for the vast majority of natives. Traditional courtyard houses were built on two key elements: materials that were readily available and the maintenance of privacy in the home. Houses often had multiple entrances, one for guests and one for its tenants. Houses were designed insularly, open spaces and yards were in the center of the house. The dwelling itself acted as a barrier for the yard. Allowing its tenants to exercise their daily lives with relative ease. As practitioners of Islam, privacy is a critical need for family living. Ensuring that there are spaces where the women of the family are comfortable and do not have to worry about the male gaze was of vast importance to the communities of this region. Additionally, people relied on natural ventilation through vernacular architecture to cool down their houses and the sun for natural lighting. This meant that the orientation of the building itself was important, ensuring that certain built elements can capture wind to cool down houses, as well as maximizing the amount of appropriate sunlight that was needed.

“Traditional stone-built houses in Najada” - Daniel Eddisford in Traditional Domestic Architecture of Qatar

The British presence in the region had a significant impact on the urban form, the lack of formally educated natives to work as technicians and specialists in the oil sector meant that many British and American engineers had to be recruited to the region. Housing built for foreign engineers were naturally modeled after housing units they were most familiar with: the villa. Additionally, building regulations at the time were heavily modeled after British standards, as a result, our regulations accommodate a certain urban form much better than the native urban form. For many residents, the old urban form became a visual reminder of poverty. It carried a great sense of misery and anguish. Particularly during a time where the pearl diving industry was hit hard by the Great Depression, Japanese artificial pearls, and a reduction in yield from pearl banks, the sole lifeblood of the regional economy could not provide basic sustenance for Khaleejis. Consequently, eyes were turned to the villa, as a new and modern way of living. One which symbolized wealth, prosperity, and ultimately status. The villa would become a showpiece. Western-design influences were a sign of sophistication, privilege, and class. The view towards traditional houses was less than pleasant, tied to poverty. Increasingly, natives left the urban core where traditional courtyard houses were and moved to the suburbs with newly built villas. The traditional urban core was torn down in some instances, put in its place are commercial apartment buildings to house a new foreign working class. In other instances, traditional houses were crumbling due to their old materials and poor maintenance. You’d be hard-pressed to find any courtyard houses in the average suburb of Doha.

The shift towards the villa created a shift in the cultural definition of privacy in the Khaleeji housing unit. A single-family villa enclosed by four walls with a front yard and a backyard. Our definition of privacy changed from a communitarian one to a personal one. The courtyard house had many layers of privacy that could be peeled back, the home was designed in such a way to have designated spaces for guests that would transition into a private spot. Conversely, the villa was completely private. It did not allow for any manner of flexibility, and once you step out of the confines of the walls of your house you enter the public realm. This means a guest entering your house occupies a space that was designed to be completely private, whereas the courtyard house can protect your personal privacy while creating a space that exists between the public and private realms. Additionally, the villa does not make good use of private open spaces. As opposed to traditional courtyard houses, the yard of a villa is regulated to either the front or back of the house. Meaning that ancillary buildings that may be occupied by ‘strangers’ limit who can and can’t use these open spaces and during which times of the day. This issue does not exist in the courtyard house. Courtyard houses were built in a way to cool down open spaces either through wind elements or casting shade onto the yard. It is not always that a villa will cast a shade onto your yard. Moreover, the management of space, electricity, and water tends to be very poor in a villa. Yet, despite both the environmental and the sociocultural consequences of this housing unit it continues to dominate our urban fabric. This raises a concern for urbanists such as myself, do our building regulations promote this type of housing unit, without giving room for architects and designers to accommodate these social needs?

Looking at current regulations for R1 Zones in Doha, which is designated as low-density residential zones, the front setback for the average plot is set at 5 meters. The side setbacks are set at 1.5 meters without windows and 3 meters with windows and if the wall faces a street the side setback is also set at 3 meters. The back setback is also set at 3 meters. The build cover area is 60% and the floor to area ratio (FAR) is 1.65. I partnered up with Salman Al-Sulaiti, an old friend and a brilliant architect out of California Polytechnic State University to explore whether or not current building regulations allow courtyard houses to be built, and could it possibly explain the dominance of the ‘Villa’ in modern urban developments.

We adopt a ‘communitarian’ definition of privacy as within the context of local traditions and religious lifestyles of the Khaleej it is a critical step to understand the advantages courtyard homes have to regional living. Using a religious framework, we develop an accurate spatial definition of privacy. With this in mind, we define the range between the public and private realms through the level of comfort in which women can present themselves when choosing to wear a hijab or a niqab (face veil). In public spaces, where people are exposed to the foreign gaze, Muslim women will often choose to cover themselves by way of scarves and veils. The next layer we define is the semi-private spaces, which acts as a reception for guests. These spaces will often be a meeting point for female visitors and extended family members (excluding male in-laws). In these spaces, Muslim women do not have to uphold the expectations of covering themselves, but because of the accompaniment of guests, there is a certain expectation in presenting themselves. In private spaces; where you are only exposed to direct family members, there are no expectations for dress and they act as spaces where you can find absolute comfort.

Diagram courtesy of Salman Al-Sulaiti (2021).

Using this religious framework to apply a spatial definition of private and public realms, we analyze the differences between the different modes of living through the following renders and illustrations. We define the ‘public’ zone as any area which exposes the tenants to the foreign gaze. The ‘semi-private’ are zones within the house that are designed with guests in mind. While the ‘private’ zones are exclusive to the tenants of the house. We work with a 600 square meter plot in a typical R1 Zone you would find in Doha, outlined below. We hypothesize that the villa’s dominance in the Qatari urban landscape may not entirely be due to preference, but due to regulations. Setbacks in R1 zones require you to keep open spaces in front of the house, this forces developers to build into the villa-style to maximize the build area, otherwise, you waste space. In the first example, Salman provides us with a typical villa and mapping out the private, semi-private, and public spaces.

Model of a typical Qatari villa, Salman Al-Sulaiti (2021).

Diagram of spatial privacy in the villa, Salman Al-Sulaiti (2021).

We found that the villa lacks open spaces that are either semi-private or private, meaning that not all tenants of the house would be able to exercise absolute freedom within open spaces. This mode of living is not at all suitable for the cultural needs of the Qatari house. The front setback of the house forces developers and homeowners to take advantage of the front yard and make it into an open space to maximize their build area. We then tried to develop a courtyard house within the framework of existing regulations and setbacks.

A modern concept of the Qatari courtyard house under current regulations, Salman Al-Sulaiti (2021).

Spatial privacy of the Courtyard house under current regulations, Salman Al-Sulaiti (2021).

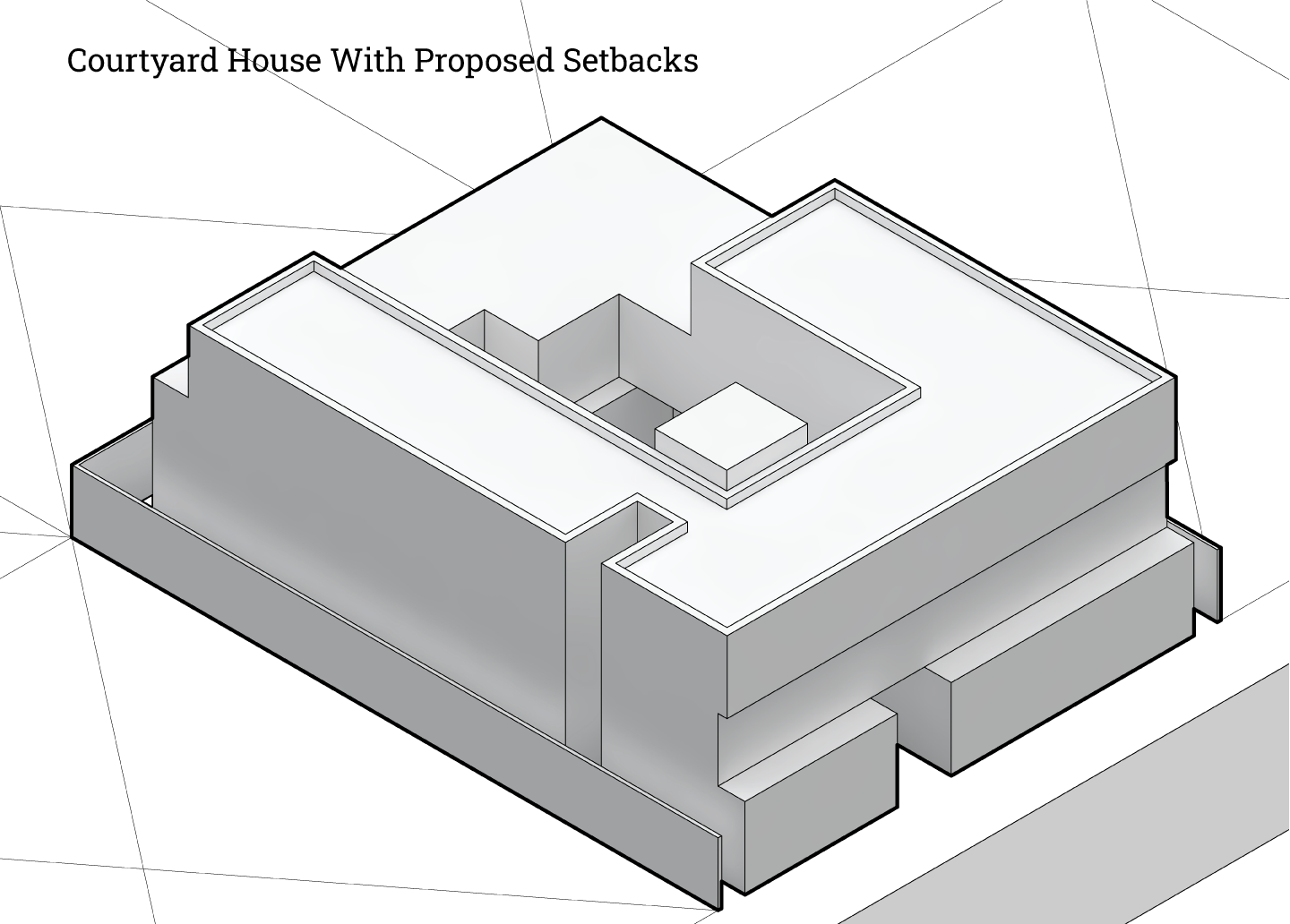

As illustrated by Salman, current regulations do not accommodate the courtyard house. While the total built area and the open space area are equal, you get a sliver of private and semi-private open spaces, at 31.5 and 46.5 meters squared respectively. Theoretically, you could increase the size of the courtyard, but it would come at the cost of your built area. This front setback makes it incredibly inefficient and impractical to build into the courtyard house style. Under proposed setbacks at the street level, while maintaining total build area. Not only do we allow the courtyard house to maximize the built area, but it also allows for private open spaces to flourish.

A modern concept of the Qatari courtyard house with proposed setbacks, Salman Al-Sulaiti (2021).

Spatial privacy of the Courtyard house with proposed setbacks, Salman Al-Sulaiti (2021).

Essentially, current regulations force homeowners and architects to build in the style of the villa. Regardless of whether or not it meets the cultural needs of our society. Designers and homeowners should have a choice in what style of living they want to adopt.

The zoning regulations in the Qatar National Master Plan outlines the idea that courtyard houses should have a separate setback, but looking at the existing framework and regulations that we build on, it has yet to be adopted. Through this exercise and experiment, I and Salman hope to illustrate how these regulations do not meet the cultural demands of Qatari society. Both the state and the people are very keen on preserving and in some cases, reviving the cultural traditions of our people. Whether it is through awareness of folkloric traditions, the sea shanties of pearl divers and merchants, and most certainly within the field of architecture. However, we should think beyond just preserving old buildings and architecture, and start thinking about reviving practices that allow us to live the way we want to. Through these diagrams and illustrations, we make the argument that it simply cannot be done now. If the concern that changing setback regulations would alter the environment and ruin the quiet suburban feel, we must remember that Khaleeji architecture, natively has always been low-density. Very rarely have buildings ever exceeded three stories, two-story houses were a rare sight too. Our indigenous urban environments have always had a certain quiet suburban field to them, and the form residences took best suited the needs of the people. Famed Qatari architect Ibrahim Jaidah writes in the opening pages of ‘The History of Qatari Architecture’:

“Architecture is not only related to buildings but represents the identity of peoples and civilizations... The qualities and features of architecture in the Islamic world set it apart from all other architecture Its most outstanding feature is the focus on interior spaces as opposed to on the outside or the facade.”

We are undeniably a Muslim nation, our national and cultural identity is integrally linked to our faith. Yet, our residences and architectural modes do not at all represent this identity, nor does it allow for our practices to flourish. The question asks itself then: why do we continue to embrace it? We have a responsibility, as designers, planners, and policymakers to consider these questions and tell ourselves: the choices that we make play an active role in what cultural practices die, and how foreign ones (which do not suit the cultural or physical environment) come to replace them. There is no denying that there are people out there who enjoy the facade and the lifestyle provided by the villa, but is that cost worth killing our own cultural identity over, and is it worth stopping a possible revival? Especially when laxing these regulations allows individuals to make these choices for themselves.

This article was written in collaboration with Qatari architect, Salman Al-Sulaiti. Please support him and follow him on Instagram: @sgalsulaiti