The Feasibility of Walkability in Extreme Heat

Courtesy of Kammutty VP, The Peninsula Qatar

As a student of urban planning in Doha, the question I get asked the most by friends and family at home is: “How do we solve this traffic epidemic we have?” Doha, and by extension Qatar and its neighbors in the GCC, all suffer from the same issues in mobility perpetuated by their auto-centric design, inefficient public transportation modes, and a lack of pedestrian infrastructure. Gulf cities suffer from extreme automobile dependency, there are no alternative means of transportation or movement other than the private automobile. Walking is the forgotten mode of transportation in the Arabian Peninsula. Citizens are already paying the cost of these urban design policies and plans. Not only have the rate of car accidents and traffic increased during recent years compared to the past, but the population of the region has gotten unhealthier. In a 2012 report of the world’s heaviest nations, Kuwait was ranked as the world’s second-heaviest country, while Qatar, the UAE, and Bahrain ranked fourth, sixth and tenth place respectively. Automotive dependency has brought traffic and health consequences in the region.

Cities of the region have followed the American planning model, designed as pedestrian-unfriendly streets following a gridiron layout. The only spaces available to walk are malls, urban and national parks, and promenades. Public transportation in the region is also severely lacking, Riyadh for the longest time lacked a mass-transit system (specifically it's metro), while Dubai’s metro serves tourists primarily. The GCC is undertaking massive steps into becoming more walkable cities and have invested billions of dollars into their public transit infrastructure. The biggest hurdle for cities in the region to overcome is that of its extremely harsh hot climate, what are the current struggles facing cities of the region to become walkable, what strategies and projects are being implemented in an effort to become walkable, and how feasible are they, I.E. can people actually walk in this stupid unbearable heat?

A study published at the King Fahad University and the University of British Columbia assesses the travel conditions and accessibility of walking as well as the willingness to walk within the Doha & Dana districts of Dhahran in Saudi Arabia. The study surveyed 200 respondents on the preferred mode of transportation to carry out certain activities, such as grocery shopping, banking, going to school, etc. The investigation shows 42.5% of residents prefer walking, of which 91.5% typically walk up to 1 km daily. The remaining 8.5% walk between 1-2 km. GIS analysis shows that 77.4% of streets in the two districts have sidewalks or walking trails (82.9 km out of 107 km of street distance). Moreover, existing sidewalk conditions in Doha & Dana are poor, sidewalks are narrow, standing at less than a meter wide, often with street lamps, signage, or date and palm trees erected in the middle, further congesting the walking trails. The study also states that 24% of the sidewalks were seen to be occupied by parked vehicles of the surrounding residents. A further 21% of the sidewalks have permanent constructions including walking ramps and carports. The study found that 60% of the residents walk to their nearest facilities while around 65% walk for recreation and health benefits. Overwhelmingly, the study shows that the most cited reason for not walking is due to the weather, daily average temperatures within the region almost reach 50°C (122°F) with very high humidity levels during the summer, pedestrians surveyed within the study area predominantly walk during the winter season.

Bahrain has taken initiative to increase activity levels and walkability through built environment measures like the national network of public recreation areas, encompassing parks, walkways, and corniches. Outdoor walking facilities are built in new residential areas and are being developed in older residential quarters. Pursuing physical activity in Bahrain is limited by weather conditions like other nations within the region suffering from extreme heat. However, citizens can be found walking outdoors in purpose-built and vacant areas around sunrise and sunset, even during the hot season. This suggests that willingness to walk during the summer season should be a subject of further investigation. Responders of the previous study showed that weather was the biggest concern, but the case study of Bahrain suggests that given the proper infrastructure, citizens can make the choice to walk in that weather. While the weather is a factor in why people choose not to walk, a lack of proper infrastructure acts as a barrier that does not allow for walking.

Courtesy of tai_mab, Flickr.com.

An article published by Qatar University in the Case Studies on Transport Policy compares pedestrian behavior during the summer and winter seasons in the Al-Sadd district of Doha. Al-Sadd is one of Doha’s most popular and livable neighborhoods, it's also known for its mixed land uses and high density. Overall, almost double the people were observed walking during the winter season versus the summer season. It is worth noting, however, that the same number of pedestrians were observed during the weekend and weekdays during the summer season, while during the winter more people walked during the weekday. Observations in the study cite that more pedestrians were recorded holding bags during the winter season, showing that small trips for shopping on foot are more favorable during the winter. A separate study from Qatar University looks at the Al-Markhiya district in Doha. Al-Markhiya offered a great deal of potential to be a self-sustaining neighborhood in Doha, with commercial frontage on Khalifa Street. Khalifa Street connects the C-Ring and D-Ring roads, and congestion issues are quite prominent on this road as commuters use this arterial road to travel from Al-Dafna to Education City. However, due to a lack of land use management and sidewalk design, this community did not realize its potential. The streets of the district are designed for the automobile, and not for pedestrians. The scale is inappropriate for pedestrians, and there is a lack of shading and street furniture discourages walking as a mode of transport.

Abu Dhabi, like Riyadh, Baghdad, and Islamabad, feature large wide arterial roads connecting in a grid pattern to define a superblock. These superblocks were to be evenly spaced creating rectangular blocks of 900 by 600 meters. Each superblock was designed to be easily navigated through direct routes, and each would function as largely independent communities with facilities and services such as schools, mosques, and small commercial developments where you could fulfill your daily necessities. Fast non-local traffic was kept on arterial roads that defined the superblock, whereas inner roads were calm to ensure a safe and protected environment for pedesterians and slower local automobiles. While Abu Dhabi largely erased any trace of its historical organic settlement pattern for the superblock system, it adopted the system of sikkak (sing. sikka). Sikkak are a system of narrow alleyways connecting the main road or city center to the surrounding residential clusters, they are very common in Arab cities throughout history and today are most prominent in historic cores of Arab cities. In Abu Dhabi, sikkak work as pass-through spaces, connecting secluded spaces of an area. A study published by Masdar Institute shows that this system of sikkak contributes tremendously to the efficiency and directness of routes, encouraging walkability within these superblocks.

Figure on the left showing the components of the superblock. Figure on the right showing the aggregation of superblocks forming a large district/neighborhood. Courtesy of M. Scoppa et al.

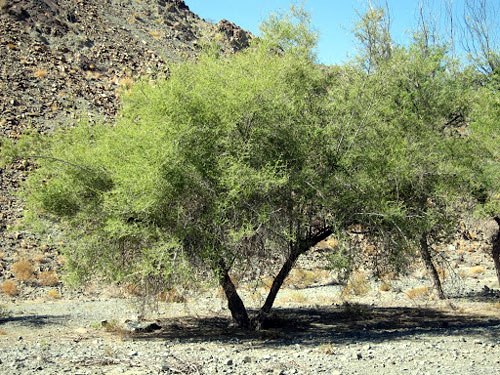

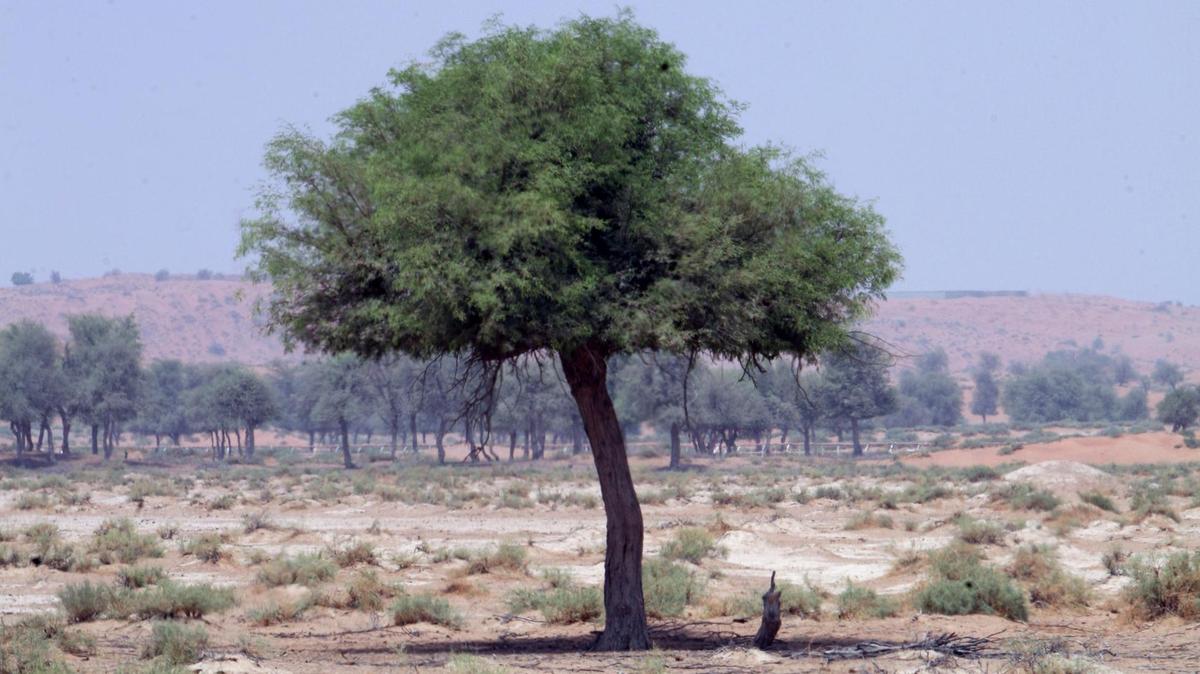

Additionally, using clever street orientation relative to the sun path, sikkak and streets can be used to create a pedestrian microclimate that would provide thermal comfort. Sikkak were designed with walls in mind to provide shade to pedestrians. Streets with a high aspect ratio (building height/street width), similar to older Arab city centers, provide a more comfortable microclimate. A study looking at thermal comfort and walkability in the Mega Kuningan Superblock in Jakarta concluded that in a hot-humid environment it is imperative that architects and city planners provide shade either from surrounding buildings or through trees. While the desert climate may discourage gardening and planting trees for shading, trees native to the Arabian Peninsula such as Samr; Sidr; Ghaf; Sind (Gum Arabic tree); Date Palms; and many more. These trees offer shade while still being able to live and prosper in the harsh desert climate.

Yes, the Arabian Peninsula is hot, unbearably hot, so hot that at times I question whether or not civilization belongs in this part of the world, but the fact of the matter is: people have lived in these areas for centuries under these difficult weather conditions. People of the peninsula relied on their feet to get around their cities and townships. Cities were dense, sikkak provided shading and additional spaces for walking, marketplaces provided shade for customers and passersby. People built malaqif (sing. Milqaf, windtowers) to cool their houses and mosques. Today, with science and technological advancements, using proper street orientation, a system of sikkak, and providing shading with trees native to the region, it is possible to repopulate our cities with pedestrians despite the heat. While the heat and weather certainly make walking less comfortable and less of an appealing option to navigate the city, the lack of infrastructure and pedestrian-oriented design bars people from walking in the city. Municipalities within the region need focus on planning at a microscale, focusing on small districts and neighborhoods, ensuring the scale of planning is that of the pedestrian such that a safe and comfortable environment can be ensured. The region is suffering from a health crisis. Obesity rates are at the highest they have historically been, cardiovascular diseases are on the rise, all of which is further stimulated by the unhealthy automobile-dependent lifestyle that the Khaleeji urban form has perpetuated. The world is suffering from an environmental crisis, countries of the GCC top the world’s lists in carbon footprint per capita, of which transportation by private automobile is one of its biggest contributors. Walking, along with public transit, should be as effective, if not more effective than the automobile if we want to make it a more competitive and attractive alternative option for transportation.

On a final note, it’s really only unbearably hot between May and September, while the weather is surprisingly nice for the rest of the year.

Additional Reading:

Harb, D F. “Walk-ability Potential in The Built Environment of Doha City,” n.d., 15.

Kamel, Mohamed Atef Elhamy. “Encouraging Walkability in GCC Cities: Smart Urban Solutions.” Smart and Sustainable Built Environment; Bingley 2, no. 3 (2013): 288–310. https://doi.org/10.1108/SASBE-03-2013-0015.

Koerniawan, Mochamad Donny, and Weijun Gao. “Thermal Comfort and Walkability In Open Spaces of Mega Kuningan Superblock in Jakarta.” In ResearchGate, Vol. 3. Venice, Italy, 2014. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.4388.5766.

Rahman, Muhammad Tauhidur, and Kh Md Nahiduzzaman. “Examining the Walking Accessibility, Willingness, and Travel Conditions of Residents in Saudi Cities.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 4 (14 2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16040545.

Scoppa, Martin, Khawla Bawazir, and Khaled Alawadi. “Walking the Superblocks: Street Layout Efficiency and the Sikkak System in Abu Dhabi.” Sustainable Cities and Society 38 (April 1, 2018): 359–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.01.004.

Shaaban, Khaled, and Deepti Muley. “Investigation of Weather Impacts on Pedestrian Volumes.” Transportation Research Procedia, Transport Research Arena TRA2016, 14 (January 1, 2016): 115–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2016.05.047.

Shaaban, Khaled, Deepti Muley, and Dina Elnashar. “Evaluating the Effect of Seasonal Variations on Walking Behaviour in a Hot Weather Country Using Logistic Regression.” International Journal of Urban Sciences 22, no. 3 (July 3, 2018): 382–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2017.1403363.

Silva, Joao Pinelo, and Aamal Z. Akleh. “Investigating the Relationships between the Built Environment, the Climate, Walkability and Physical Activity in the Arabian Peninsula: The Case of Bahrain.” Edited by Silvio Caputo. Cogent Social Sciences 4, no. 1 (January 1, 2018): 1502907. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1502907.