Nature-Embedded Cities in Arid Contexts: A Khaleeji Framework

The notion of nature-embedded cities has become a fascinating and increasingly prominent topic in contemporary urbanism. The Chinese sponge city model, adopted as a nationwide urban construction policy in 2014, promotes a set of nature-based solutions that enable cities to absorb, store, infiltrate, and purify rainwater through natural and semi-natural landscapes rather than relying solely on conventional grey infrastructure.

The Nanchang Fish Tail Park, example of the Sponge City model in action. (Source: Turenscape, 2021)

Instead of rapidly channeling stormwater away through pipes and concrete drains, sponge cities seek to slow, spread, and sink water across urban surfaces using tools such as wetlands, permeable pavements, bioswales, retention ponds, and green open spaces. The concept draws from both ecological planning theory and historic urban practices developed in response to monsoonal climates in southeastern China, where cities evolved to coexist with seasonal flooding rather than resist it, turning water from a hazard into an organizing element of urban form and public space.

Another emerging model of nature-embedded urbanism is urban rewilding, which challenges the idea that nature in cities must always be highly manicured, ornamental, and controlled. Urban rewilding advocates for the restoration of native ecologies and the reintroduction of self-sustaining habitats within the urban fabric, allowing natural processes to play a greater role in shaping landscapes over time. Urban rewilding treats park and landscape design as evolving ecosystems that support biodiversity, regulate microclimates, and strengthen ecological connectivity across metropolitan regions.

A frequently cited example is the transformation of the Cheonggyecheon stream in Seoul, where a buried waterway was uncovered and restored as a linear ecological corridor, dramatically reducing urban heat, improving air quality, and reintroducing aquatic and bird species into the city center. While highly engineered in its execution, the project demonstrates how reintegrating natural systems into dense urban environments can simultaneously deliver ecological, climatic, and social benefits.

Cheonggyecheon Stream, Seoul, South Korea. (Source: @giuliaseok on TripAdvisor.com)

These models of nature-embedded urbanism share a common thread: they are largely oriented around “green” conceptions of nature rooted in temperate and monsoonal ecologies. One of the central challenges of urban planning in the Arabian Peninsula, however, lies in its fundamentally different environmental and climatic conditions. Cities of the Khaleej (and the peninsula at large) are built within hot, arid desert landscapes where water is scarce and evapotranspiration rates are high. In this context, importing conventional green models of urbanism can be environmentally counterproductive, leading to increased irrigation demand, higher energy consumption for desalination, and intensive landscape maintenance regimes that undermine long-term sustainability.

This raises an important set of questions: can nature-based urbanisms meaningfully exist in this part of the Arab world? Are there indigenous spatial and environmental practices to learn from? And how can we reinterpret nature-embedded urbanism for arid environments?

Nature-Embedded Urbanism in Pre-Oil Khaleeji Settlements

Aflaj Irrigation Systems of Oman. (Source: Ko Hon Chiu Vincent / UNESCO.org)

Long before modern drainage systems and desalination plants, communities across the Arabian Peninsula developed highly effective ways of living with water scarcity. One of the most notable examples is the aflaj irrigation system (singular: falaj), a network of gravity-fed underground and surface channels that carried groundwater or spring water from distant sources to villages and agricultural land. These systems required no mechanical pumping and were carefully calibrated to follow natural slopes. Just as important as their engineering was the social system built around them: water was shared through precise time-based allocations, and maintenance was carried out collectively. The falaj was therefore not only infrastructure, but a system that shaped settlement patterns, farming practices, and daily life around shared responsibility for scarce resources.

Around these water networks emerged oasis settlements where homes, date palm groves, and farmland were closely intertwined. Palm canopies created shade and cooler microclimates, allowing other crops to grow beneath them and reducing water loss from the soil. These landscapes were productive, climatic, and social spaces at the same time, showing that nature in desert settlements was not decorative, but directly tied to survival, comfort, and economic life.

In parallel, many communities relied on wadi agriculture and floodwater harvesting, making use of seasonal water flows rather than permanent sources. Instead of trying to block floods, people built small barriers, channels, and terraces to slow and spread stormwater across fields, allowing it to soak into the ground and nourish crops. Flash floods, while dangerous, were also opportunities to replenish soils and recharge shallow groundwater. In many ways, this was an early form of landscape-based water management, working with natural cycles instead of forcing water into rigid pipes and drains.

Nature-based adaptation in Gulf settlements was not limited to water management alone. I’ve talked about this on my blog and public talks before, but passive climatic design strategies played a huge role in making this part of the world habitable. Architectural designs that worked with heat, wind, and solar exposure to create livable environments in extreme conditions.

Al Fahidi Historical Neighbourhood, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. (Source: Yamani Alafari / Al-Bayan Newspaper)

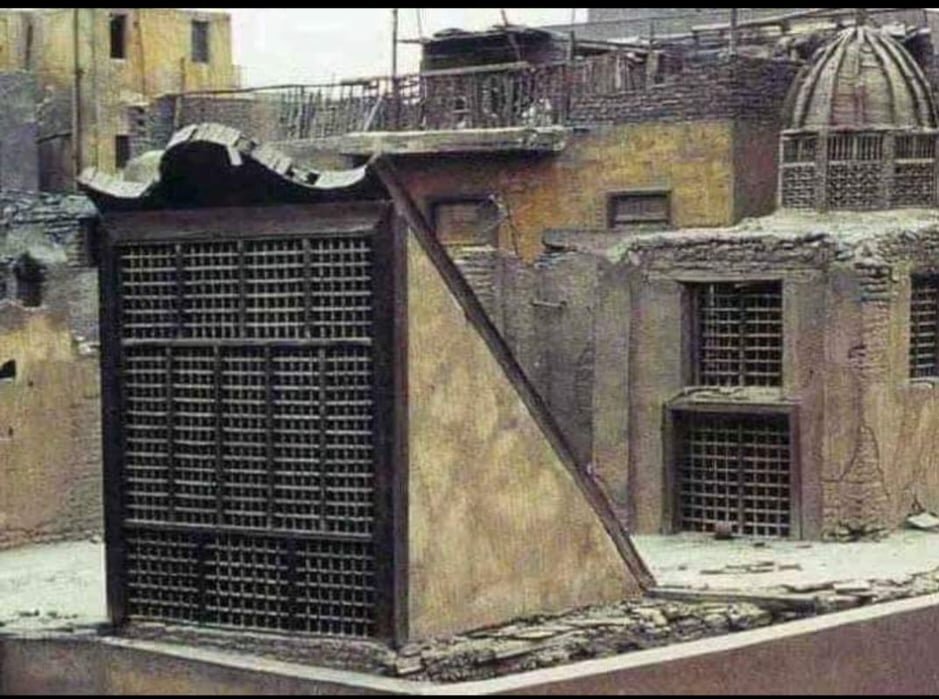

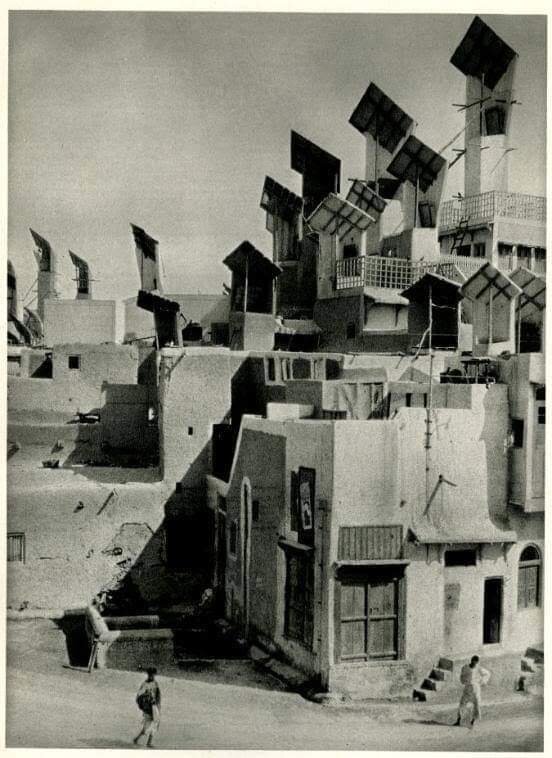

One of the most recognizable features of traditional Gulf architecture is the wind tower, or barjeel, designed to capture prevailing breezes and direct cooler air into interior spaces. Combined with narrow streets and shaded passages that accelerated airflow, these elements helped reduce indoor temperatures without the use of mechanical cooling. At the scale of the home, courtyard houses created protected internal microclimates, where shaded open spaces, vegetation, and evaporative cooling moderated heat while maintaining privacy and social cohesion.

Material choices also played a critical role in regulating comfort. Buildings were commonly constructed using locally sourced materials including: mudbrick, coral stone, limestone, and other materials with high thermal mass that absorbed heat during the day and released it slowly at night. These materials were not only climatically effective, but also low in embodied energy and closely tied to local supply chains and craftsmanship. Roofs made from palm trunks and fronds further added insulation while using readily available natural resources. In this way, construction practices were directly linked to local ecologies, rather than dependent on imported industrial systems.

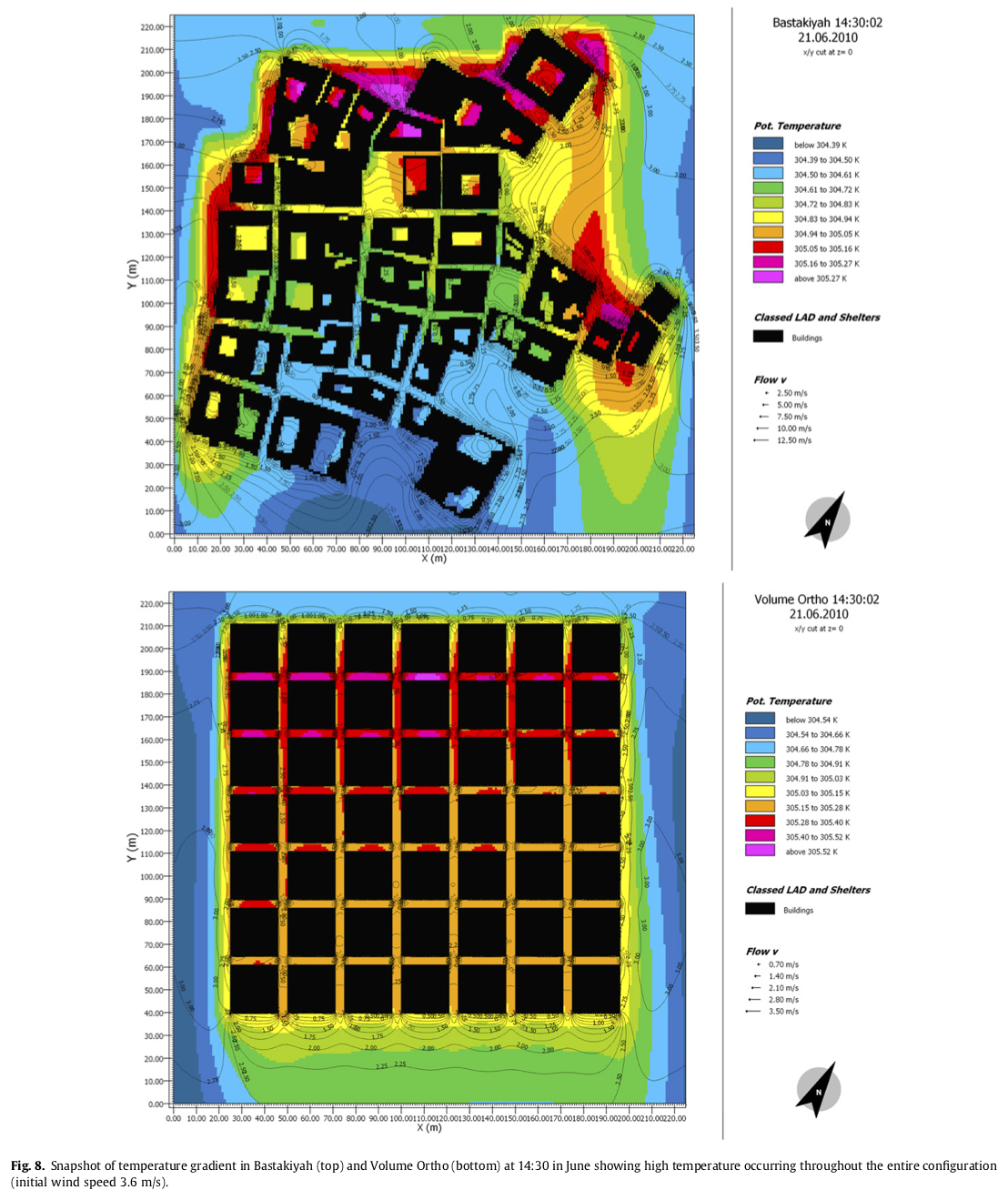

On the neighborhood and town-scale, settlement layouts themselves contributed to climate adaptation. Compact urban fabrics reduced exposure to the sun. Shaded walkways encouraged pedestrian movement, and building orientations responded to dominant wind patterns and seasonal sun paths. Together, these strategies formed an integrated environmental logic where comfort was achieved not through energy-intensive technologies, but through spatial design and material intelligence. This broader reading of nature-based urbanism, one that includes air, shade, soil, and thermal behavior, is especially relevant for desert cities today, where water alone cannot be the foundation of climate-responsive urban design.

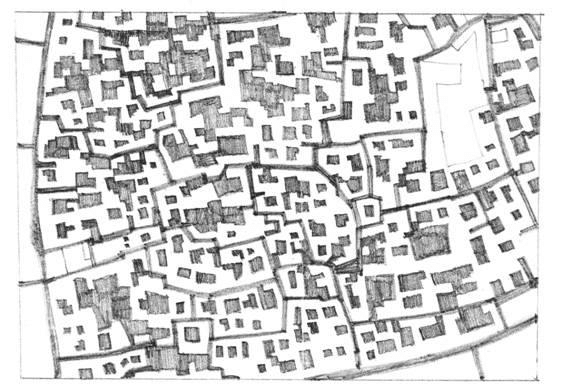

“The urban fabric of Muharraq with its distinctive features; hierarchy of open spaces, courtyards, organic form and winding roads” (Source: El-Masri and Alraouf, 2005).

Redefining Nature in Desert Cities

So how do we embrace nature-embedded urbanism in desert cities? Planners, designers, and landscape architects must answer this question by redefining what we mean by “nature” in the public realm. Landscape design in Gulf cities should not be reviewed by aesthetics and visually, by how “green” a space looks. Rather we should measure how well it performs ecologically or climatically.

Lawns, exotic trees, and water-intensive landscapes may visually signal environmental care to the layman and general public, but they come at high environmental cost in arid regions, relying on constant irrigation and energy-intensive desalination. In this context, the pursuit of visual greenness risks becoming a form of greenwashing that masks deeper ecological inefficiencies.

An example of desert xeriscape landscaping in Dubai (Source: ‘NAD AL SHEBA’ Project by Wilden).

A more appropriate approach lies in embracing desert-based and xeriscape landscaping, using native and drought-tolerant plant species that are adapted to local soils, heat, and salinity. Such landscapes require significantly less water, provide habitat for local biodiversity, and are better suited to long-term maintenance realities.

More importantly, they reflect the natural character of the region rather than attempting to overwrite it. Shaded gravel gardens, native shrublands, and desert grasses can be just as spatially rich and socially inviting as conventional lawns when thoughtfully designed and integrated with seating, shade structures, and pedestrian networks.

An example of desert xeriscape landscaping in the UAE (Source: “Private Residence” Project by desert INK).

This redefinition of nature can also extend vertically and into the built environment. Green roofs and green walls in desert cities don’t have to mimic temperate gardens. They can be planted with xeriscape and drought-tolerant species that thrive with minimal irrigation and are adapted to heat and salt-laden winds. In practice, this means selecting plants such as succulents, native grasses, hardy shrubs, and desert flowering species that require very little water and can survive long dry periods, dramatically reducing irrigation needs compared with conventional green roofs. Research into native plant palettes for Qatar and the wider Gulf has identified local species suited to urban conditions that can save around 70% of the water required by typical ornamental landscapes while still providing shade, habitat, and aesthetic value.

In Khaleeji cities, rooftop gardens should use hardy species like succulents, ornamental grasses, and shrubs chosen specifically for arid conditions, helping to insulate buildings and cool their surroundings while supporting micro-habitats for pollinators and birds. This approach allows vegetation to persist on rooftops and facades with minimal water, either through drip systems or recycled greywater.

AI Generation of what a desert xeriscape landscaped roof could look like in the Gulf (Source: Google Gemini).Perhaps most importantly, desert cities should reconsider the role of urban agriculture and productive landscapes as part of everyday urban life. Date groves, community gardens, and small-scale agricultural plots can once again become elements of neighborhood open space, reconnecting residents to food systems while reinforcing cultural identity. Historically, productive landscapes were central to settlement life in the Gulf, not peripheral to it. Reintroducing them into contemporary urbanism challenges the notion that nature in cities must be purely recreational or decorative, and instead frames it as functional, cultural, and socially embedded.

In this light, planners should advocate for the preservation of agricultural lands within urban areas, prioritizing their transformation into community gardens and productive parks rather than allowing their gradual conversion into residential subdivisions.

Such spaces can serve both environmental and social functions, supporting food security, microclimate regulation, and community engagement while maintaining links to local heritage. Planning tools such as transfer of development rights, land banking, and targeted zoning protections can be used to safeguard these lands, redirect development pressures to better locations, and ensure that productive landscapes remain an integral part of the urban fabric.

Heenat Salma Farm in Al-Shahaniya, Qatar. (Source: Heenat Salma Farm).

It is here I am reminded of the Khaleeji adage:

“.الخليج ليس نفطا، والنفط ليس عار”

… meaning the Khaleej is not oil, and there is no shame in oil. In the same spirit, we ought to say that the Khaleej is not only desert, and there is no shame in the desert. What I mean by this is not a rejection of progress or urban growth, but a call to embrace our natural heritage as a foundation for shaping our urban praxis, both scientifically and aesthetically.

Desert landscapes are not empty or hostile backdrops like we often characterize them to be, nor do they need to be corrected by imported greenery. They are complex and resilient ecosystems with their own rhythms, beauty, and ecological intelligence.

To design cities that are truly nature-embedded in this region is not to deny the desert, but to design with it, to work with its water cycles, its winds, its soils, and its seasonal extremes.

In doing so, we not only reduce environmental costs, but also recover a sense of place that is deeply rooted in local geography and cultural memory. A confident urbanism for the Gulf should not aspire to resemble other climates and other cities, but should instead draw strength from what this landscape already offers.

In embracing the desert, we may find that sustainability, identity, and resilience are not competing goals, but deeply intertwined ones.

I’ve also released a supplementary carousel post on my Instagram which proposes a couple of planting palettes to use for green roofs in Qatar, linked here! Do check it out on my personal Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/abdulrahmanalmana