Heritage, Citizen Planning, and Fostering Belonging

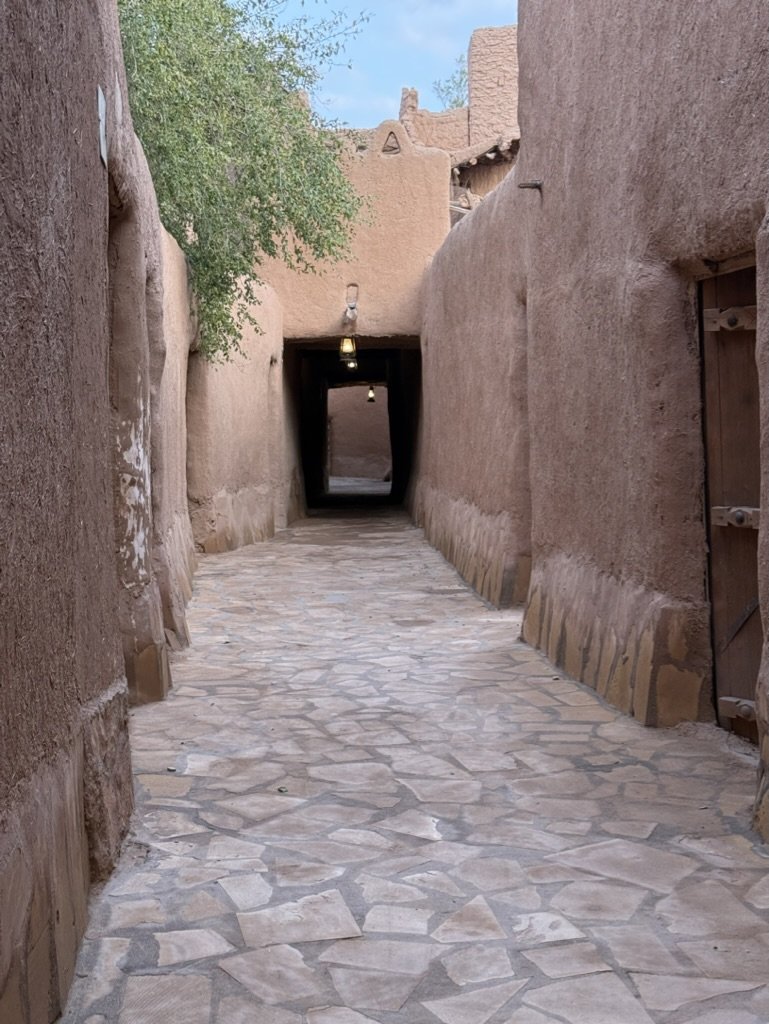

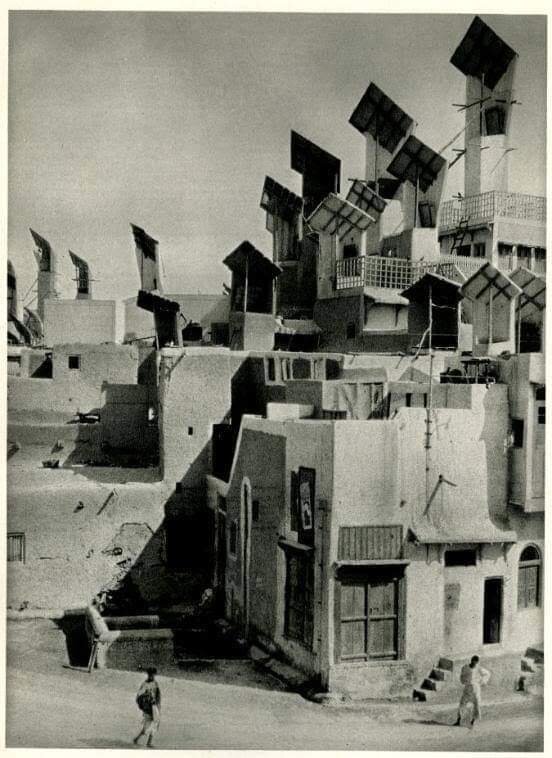

Photo taken near Qasr Al-Hokm. (Myself, 2025)

The International Society of City and Regional Planners' 61st World Planning Congress hosted in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, last week calls on "Cities & Regions in Action: Planning Pathways to Resilience and Quality of Life" to analyze, discuss, and search for better pathways for urban and regional planning aiming at improving the quality of life of citizens.

It is in this light that I'd like to share a personal story from last year - on an experience I've had, 200 km north west of the host city: Riyadh.

Most of my visits to Riyadh have only been for a few days, usually to attend a workshop, conference, meeting, or an event. On my last trip, I've decided to experience Riyadh in a completely new light - not as a city of the future, but as a city of the past, rooted in its culture, heritage, and history.

I've long been interested in heritage sites within the built form. The adaptive reuse of buildings, its activation, management, and the way that it forms the city's identity. It is for that reason, I decided to explore a village rich in history and culture, with roots to my own heritage.

Early in the morning, on a complete whim, I was exploring the area surrounding Riyadh via Google Earth, and my eyes lay on a familiar name: Ushaiqer. I had heard of Ushaiqer from family members as the origin point of our family, 200 odd years ago or so. Without doing any research on what it looks like, whether or not it had been preserved, and how easy it is to get there, I grabbed my car keys and made the drive.

I arrived in Ushaiqer around noon, right after Duhur prayer. As I was walking down its alleys, I was stunned by just how peaceful, quiet, and stunning its buildings are, and quickly started taking photos with my phone. Given my arrival time, it was no surprise that the village was empty and quiet, but from a distance I hear the sound of laughter, and I hear a voice calling for me:

“أووه، يالكشخة! تعال! اخوياي سواليفهم مثل وجيههم ما عاد ابيها. تعال اهنا ناخذ من عندك العلوم الطيبة.”

If I were to translate it, it would be something along the lines of: “Hey, style icon! Over here! I’d done with my boys and their dead chat, it’s getting unbearable. Slide over and give us the good stuff, you look like you got some good conversation!”

Dar Al-Mshraq [Al-Salem House], Ushaiqer Heritage Village. (Myself, 2025)

I walk over to his majlis and I’m astounded just by how beautiful it is. Thick mud walls the color of date syrup, edged in bright white plaster that catches the light. The ground under my feet is uneven stone, worn smooth in places, as if generations have paced the same path.

Up close, the details start to speak: a small wooden window set deep into the wall, a heavy door tucked into shadow, and above it a rounded corner tower that leans over the courtyard like a lookout. The parapet is crowned with white pointed teeth, Najdi-style crenellations, marching along the roofline in a clean rhythm. Under the overhang, rough wooden beams poke out, dark against the clay, and a few hanging lamps sit quietly in the shade, waiting for evening.

Inside, the majlis feels warm, like the embrace of an old friend, even though everyone here is a stranger. Low timber beams and packed-earth ceilings sit overhead, lantern lights casting a soft glow across mud-plastered walls trimmed in crisp white patterns. Rugs cover the floor in bold reds and geometrics, cushions line the edges, and wall niches display brass dallahs and old keepsakes, giving the whole room a quiet, lived-in calm.

Fahad Al-Salem, Abu Abdulaziz, the host and owner of the home.

The owner of the home, Bu Abdulaziz, is an interesting, charismatic figure. One of those people who makes a place feel alive the moment he starts talking. He doesn’t just greet passersby; he gathers them in, eager to share the story of his house and the village around it. He asks my name, where I’m from, and as soon as I introduce myself, he smiles and says he can tell my family’s roots trace back to Ushaiqer. I confirm it, and in that instant the distance between “guest” and “family” seems to disappear.

From there, the day unfolds like I’m not visiting at all, like I’m returning to something I’d forgotten was mine. I spend hours with Bu Abdulaziz, his brother, his nephew, and his in-laws, moving through the village as they point out the buildings that matter: old homes, gathering spaces, corners with stories attached to them. They walk me through the village’s history with the ease of people who’ve lived it, not just memorized it.

They show me the farms, how the land still holds its rhythms, and talk about the residents’ role in keeping everything standing. What stays with me most is the pride in the details: how they rebuilt what time had worn down, how they preserved the character instead of replacing it, and how care for the village isn’t a project for them, it’s a responsibility, carried quietly, like looking after your own family home.

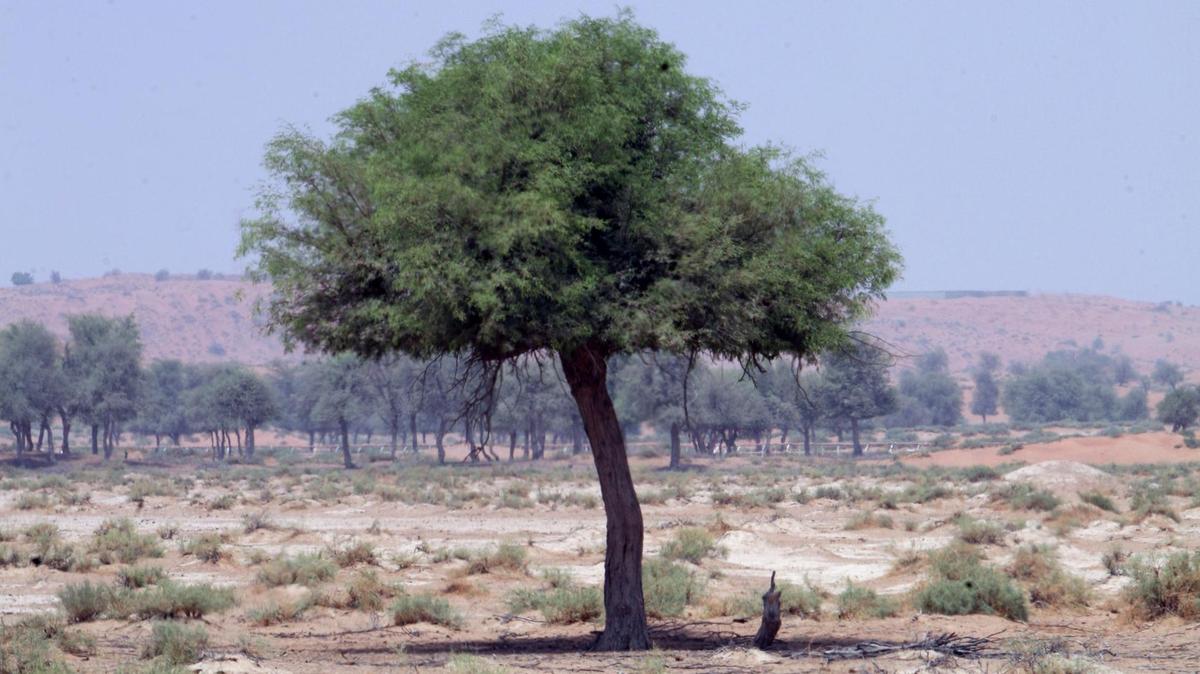

We spent the evening tucked between Ushaiqer’s dunes, the air cooling as the sun slipped away. Abu Abdulaziz filled the silence with old stories, then began reciting poetry, verses about family, history, and heritage, and the feeling of returning to where you began, as if every road eventually bends back to its origin.

What I witnessed in Ushaiqer wasn’t just “heritage preservation” in the institutional sense, it was a living form of planning, led by residents who understand the value of place because they’ve carried it in their daily lives. In a time when we often speak about resilience through infrastructure, policy, and technology, Ushaiqer reminded me that resilience is also social: it’s memory, stewardship, and the quiet pride that turns maintenance into meaning. Bu Abdulaziz and the people of the village weren’t simply restoring walls, they were restoring continuity, making sure the village remains legible to its children, and welcoming to those who arrive searching for something they can’t quite name.

Between the dunes of Ushaiqer (Myself, 2025).

This is where the idea of “citizen planners” becomes real. They may not write zoning codes or draft masterplans, but they shape the future through caretaking, storytelling, hosting, and rebuilding with sensitivity. They safeguard identity while keeping the village active, not frozen, proving that belonging is not manufactured through branding, but earned through relationships, ritual, and shared responsibility. The majlis becomes a planning room. The alley becomes a narrative archive. The farm becomes an ecosystem lesson. And the visitor, stranger, or descendant becomes part of the story the moment they’re welcomed in.

As we continue to discuss pathways to quality of life in our cities and regions, I keep returning to that evening in the dunes: poetry about family, history, and the pull of origins, spoken under an open sky. It made me reflect on how our planning practice can better honor people’s emotional geographies, not only where they live, but where they feel they belong. Perhaps the most enduring form of resilience is the one that makes a person say, even far from home:

I’ve returned.